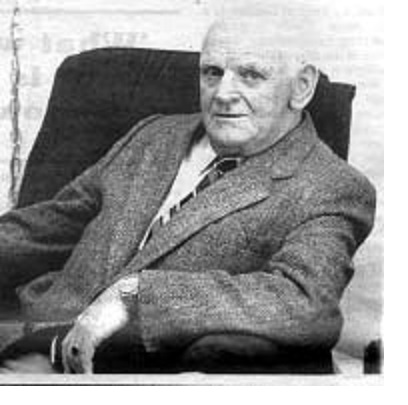

JAMES DEMPSEY, 94: RADIO OPERATOR

Newfoundlander who guided early flights across the Atlantic.

He

gave bearings to the Hindenburg and to flying boats, and played a key role in

sinking the Bismarck

Special to The Globe and Mail

February 18, 2009

by

J.M. SULLIVAN

ST.

JOHN'S -- In an era when Newfoundland was on the world's military strategic cusp

and a global commercial crossroads, James Dempsey was a wireless operator and

radio technician whose telegraphing skills allowed him to play vital roles in

many of the triumphs and the tragedies of pioneering transatlantic commercial

and wartime flight. He helped to guide the first commercial flying boats from

Ireland to Newfoundland, and once even gave bearings to the famed, doomed

Hindenburg.

ST.

JOHN'S -- In an era when Newfoundland was on the world's military strategic cusp

and a global commercial crossroads, James Dempsey was a wireless operator and

radio technician whose telegraphing skills allowed him to play vital roles in

many of the triumphs and the tragedies of pioneering transatlantic commercial

and wartime flight. He helped to guide the first commercial flying boats from

Ireland to Newfoundland, and once even gave bearings to the famed, doomed

Hindenburg.

As

the Second World War loomed, he was one of the first radio staff on site of both

the new Botwood seaplane terminal and the fledgling airfield at Gander, where he

became involved in the surveillance of German U-boats lurking in the North

Atlantic. Gander was also the vital liftoff point for the Royal Air Force's

Ferry Command, which, beginning in 1940, organized the transit of more than

20,000 North American- built fighters and bombers to fighting destinations in

Europe.

"The radio operators were pretty amazing," said Lisa Porter, a screenwriter who

interviewed Mr. Dempsey as part of the research for the award-winning TV series

Above and Beyond, which chronicled wartime Gander. "They were the first ones

there. The precursors to air traffic controllers. They were wireless operator

with Canadian Marconi on Signal Hill; these studies lasted six months and were

capped with a written exam at the Post Office. He passed in 1935.

His

first position was with Crosbie and Co. on the Imperialist, a deep-sea trawler

with a cargo of salt bulk fish and a crew of 60. He was also posted to the SS

Dasey, which was chartered to sail Newfoundland's Anglican bishop, William

Charles White, along the coast to conduct his annual summer confirmation tour.

Stints on various other boats followed until 1937, when was hired to work in

Botwood.

In

1935, the British, Irish and Newfoundland governments had met in Ottawa and

agreed to develop regular transatlantic mail and passenger services on "flying

boats," and Botwood, population 1,000, was selected as the location for a

seaplane terminal. Botwood had been earmarked as a potential aviation hub by

Charles and Anne Lindbergh in 1933, when they visited the town during an

extensive survey for the U.S. government. The town is located near the end of a

long, narrow harbour in Notre Dame Bay, along the great circle route between

London and New York, and already had an aviation history: In the early 1920s, an

Australian First World War veteran named Major Sidney Cotton kept three planes

there that he used to deliver mail and for reconnaissance in spotting seal

herds.

In

1933, British Imperial Airways won exclusive rights for transatlantic flights

and formed an agreement to share this prospect with Pan American Airways. In

1937, the "clippers of the skies" of Pan Am and Imperial began experimenting

with passenger and mail travel. Dempsey was in the second set, with William

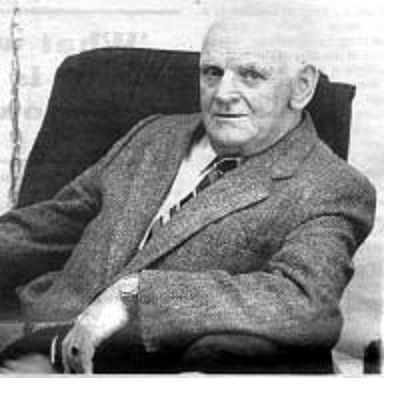

Heath. Mr. Dempsey worked as a ground-to-air radio officer, as well as flying

with pilots who were calibrating radio direction finders for landing on nearby

Gander Lake.

As

a ground-to-air radio officer, Mr. Dempsey was on hand for the birth of

commercial flights across the North Atlantic. On July 6, 1937, the Pan American

Clipper III, then the largest airplane in the world, left Botwood for Foynes,

Ireland, just as the Imperial's Caledonia left Foynes for Botwood. Mr. Dempsey

was in contact with the Caledonia within 15 minutes of liftoff and maintained

contact throughout the flight. It was flying at 2,000 feet, with headwinds

sometimes reducing its speed to as slow as 90 knots. "I directed it into

Botwood," Mr. Dempsey later told the Gander Beacon. "There were four bearings a

minute on the final approach to Botwood. There was no instrument landing system

or radar in use in those days." He also directed the Clipper III on its 16-hour

journey in the opposite direction.

More than two years of test flights followed. Then, on Nov. 30, 1938, Botwood's

weather-forecasting office was relocated to Gander. As the radio operation was

so closely connected, it moved too.

Gander became an operational airport with four runways that year, the only such

facility is what is now Atlantic Canada. Gander International Airport was a

modernist gem of architecture and design, a showpiece with a special VIP lounge

for the more glamorous of the travellers - Marlene Dietrich, Bob Hope, Ingrid

Bergman, Marilyn Monroe - on the Christoph V. Doornum was docked in Botwood's

harbour, loading ore concentrate from the Buchans mine. Locals joined

the

Newfoundland Constabulary to seize the ship and imprison the crew.

Meanwhile, with the only functioning airport in the North Atlantic region,

Gander became an important strategic point for military manoeuvres and Ferry

Command. Europe needed planes, but they could not be shipped, considering the

dangers of U-boats. The planes were too valuable pieces to expose to torpedoes -

they needed to fly, and Newfoundland was well positioned as a refuelling point.

At

the time, the RCAF controlled both Botwood and Gander, and Mr. Dempsey worked

for the British Air Ministry. The primary task was to keep bearings on German

submarines. Each shift brought lists of frequencies and schedules for listening,

but never the names of the targets. The radio operators just knew they were

taking bearings on German battleships, destroyers and U-boats. Sometimes,

however, they got an inkling of their targets. When the Bismarck was sunk on May

27, 1941, Mr. Dempsey reviewed the logbooks and suspected that he and a Bermuda

operator had helped to plot the feared German battleship's location. Mr. Dempsey

never tried to pursue any recognition for this, and the Royal Air Force later

destroyed all the logbooks.

In

any case, the radio operators knew their work was important. By 1942, German

submarines were actively prowling the Strait of Belle Isle and moving along the

Gaspé coast. Gander was the scene of many aviation calamities too. Among them

was the 1941 death of Major Frederick Banting, co-discovered of insulin, who was

on a Hudson Bomber that had taken off for Scotland before crashing near Musgrave

Harbour.

Such were the perils of war, but there were benefits too. "We were a colony and

there is no question that World War II brought us into the aviation realm," said

Nelson Sherren, a former pilot and aviation historian. "World War II really

started industrialization in Newfoundland, excepting a couple of pulp and paper

mills, but this began our training of tradespeople and engineers. And Botwood

and Gander were part of the war effort that was very important to the Allies."

The

end of war didn't mean the end of drama for Gander or Mr. Dempsey. For example,

on Sept. 18, 1946, Sabena Airline DC4 flight 00CBG from Brussels to New York

with 44 on board crashed at Dead Wolf Brook. With 18 survivors and 26 dead, it

was the world's worst air crash to date, and he was part of the team that helped

to locate the crash site and co- ordinate the complex rescue.

With Confederation in 1949, the Canadian government took control of the airport,

and Mr. Dempsey found himself working for Transport Canada. With the jet age,

transatlantic flights no longer needed to stop in Newfoundland for refuelling,

but Gander remained a viable airport. Mr. Dempsey was radio supervisor from 1948

to 1953 and then worked as a radio technician until retiring in 1973.

After retiring from Transport Canada, he worked in documenting the unique

chapter of Newfoundland's wartime history.

Jim Dempsey and his world of

radio communications

Reproduced with

permission from The Beacon Supplement July, 1987

Contributed by

Carol (Mercer) Walsh - Class 1954

Still

vigorous, chatty and intensely alert for his 72 years, retired Transport Canada

radio operation and Brochen Street resident James Dempsey is a familiar figure

as he strolls around town with his half-century of memories. And, to know his

background is to know how Gander emerged, for he was one of a small contingent

of communications pioneers who were there from the very beginning.

Still

vigorous, chatty and intensely alert for his 72 years, retired Transport Canada

radio operation and Brochen Street resident James Dempsey is a familiar figure

as he strolls around town with his half-century of memories. And, to know his

background is to know how Gander emerged, for he was one of a small contingent

of communications pioneers who were there from the very beginning.

Particularly, he has fond memories of the old townsite which,

despite modern day Gander, he has missed greatly. “It was much smaller and

closer,” he recalled of this airport fringe community that was a forerunner to

the Gander that is seen today.

His roots, naturally, are with the past and besides his

lifelong dedication to aviation and marine communications, he also cut out a

niche in history as an early community liquor-licenced club associate, as well

as in sports. For these outstanding endeavors he has been officially

recognized.

A native of St. John’s, his mere surname suggests his Irish

extraction, but his lively and witty personality confirms it the more. “It was

the smartest move I ever made to get out of there,” he smiles, in relation to

St. John’s but his remark, of course, is in retrospect and more than a

criticism, it speaks for the satisfaction he has gotten out of his life at

Gander.

His initial interest in communications came when he

apprenticed, free of pay, as a radio wireless operator with Canadian Marconi at

Signal Hill, under Superintendent Jim Collins, father of the present Minister of

Finance. It took six months following which he wrote exams at the post office

and passed under examining Officer Jack Crocker.

This was 1935 and his first job was with Crosbie and Co. on a

deep sea trawler named Imperialist, which handled salt bulk fish only since

refrigeration had not then come into its own. The 60 man crew was half

Newfoundlanders and half French.

Later, he would take other jobs to carry him through the

year. One was on the S.S. Dasey, a vessel chartered to take the Anglican Bishop

around the coasts of Newfoundland on his annual summer confirmation tour.

Following this he joined the Marie Yvonne under Capt. Jim Bragg, which was

engaged to search for the John Henry Madill, a newsprint carrier owned by a

publishing company in Chicago. Enroute from England, the all welded ship was

never located.

This took him into 1936 and over that year he would be radio

operator on the seal S.S. Thetis and after that be involved in copying wireless

press for the Daily News and St. John’s Evening Telegram under contract C.B.

Scott.

In

1937, too, he turned to the sealfishery for work, this time on the S.S. Neptune,

a well known vessel.

In

1937, too, he turned to the sealfishery for work, this time on the S.S. Neptune,

a well known vessel.

It was his association with Mr. Collins of Marconi that would

eventually bring him in contact with Gander but, first, he was hired for

operations at Botwood, which precluded construction of an airport in an area

that was becoming known as the Newfoundland Airport, then Gander.

Being in the field of communications, Squadron Leader H.A.L.

Pattison, who headed up operations at Botwood, knew Mr. Collins and inquired of

the later whether there were wireless operators available, for there was

employment for them at Botwood, where the first flying boats across the North

Atlantic were to make their debut.

One such position was offered to Mr. Dempsey, which he gladly

accepted but not until he had visited Signal Hill to say goodbye. It just

happened that a service was needed so he chipped in, again free of charge, and

gave a bearing to a German ship - The Hindenburg.

“That’s the last thing I ever done free gratis,” he recalled

lightly of his work on Signal Hill.

He arrived at Botwood May 6, 1937 to find five English radio

operators putting a station together. Newfoundlanders were being taken on in

pairs and the first two to be hired were Vincent Myrick and Art Pittman,

following which Mr. Dempsey and William Heath, an Englishman already established

in Newfoundland, were hired. Then, there were Fred Lewis and Bill Lahey; Jim

Strong and Charlie Blackie, in that order. Once the core was in place, men were

hired in singles.

Among Mr. Dempsey’s first assignments was flying as a radio

operator with Capt. Doug Fraser who would become, in time, the first pilot to

land at Gander airport. They were calibrating radio direction finders for

landing on Gander Lake.

Among his first duties as a ground-to-air radio officer at

Botwood was to direct the first commercial flights across the North Atlantic on

July 6, 1937.

There were two flights, one a short Sunderland flying boat of

the Imperial Airways, which left Foynes, Ireland for Botwood at 5 p.m. The

first contact was made 15 minutes after being airborne and it was maintained

right through to Botwood. It was flying at a height of 2000 feet and speed was

reduced to 90knots at times because of headwinds.

“I directed it into Botwood,” he said, “there were four

bearings a minute on the final approach to Botwood. There was no instrument

landing system or radar in use in those days.”

On the same day he directed a Pan American Clipper which left

Botwood enroute to Foynes, the opposite flight, taking 16 to 17 hours. Mr.

Myrick did Botwood, Ireland and New York, with point to point conversation

The second Atlantic commercial flight landed at Gander Lake.

For this, Mr. Dempsey was posted to Glen Eagles, a position at the lake. He was

located in a camp with a radio transmitter and receiver. He remembered that

Hugh Lacey was the weather observer. Mr. Dempsey didn’t think there were any

flights in 1938 but flights did resume in 1939.

On

November 30, 1938, the weather forecasting office at Botwood ceased to be, for

Gander by now, was showing its potential as an airport so the weather operation

was moved to Gander. That meant that radio operations, being closely related,

moved as well. In all, there were about 40 people working in operations at

Botwood.

On

November 30, 1938, the weather forecasting office at Botwood ceased to be, for

Gander by now, was showing its potential as an airport so the weather operation

was moved to Gander. That meant that radio operations, being closely related,

moved as well. In all, there were about 40 people working in operations at

Botwood.

The day on which was transferred to Gander there was a foot

and a half of snow. His wife, Vera, the former Vera Greene of Bishop’s Falls,

arrived at Gander in February of 1940. (They have three children, Patricia,

Helen and Jane).

He was working for the British Air Ministry and the young

family (they had only Patricia at the time), obtained an apartment, as part of

the location of the radio receiving station. The area is now referred to as the

Old Navy Site. For transportation, operators used an enclosed shed, eight feet

by six and six high, which contained a stove and a lantern and was drawn by a

tractor.

His work, needless to add, was war-oriented and mainly, the

task was to keep bearings on any German submarine and report bearings to the

Canadian Navy. Mr. Dempsey kept a diary, a notebook of daily details of his

work, but destroyed the information because it was privileged.

He remembers 1942 quite well. He would keep bearings on

German submarines, which had entered the Strait of Belle Island were operating

between there and the Gaspe coast, then report the information to the Canadian

Navy which, at first, did not believe such activity existed.

The sinking of Allied ships, however, soon confirmed as much,

there was a period between September and October that year, when war was very

threatening in the Newfoundland and Canadian waters and it was impossible to

know what would happen next. It was the time when three ore carriers were sunk

at the pier at Bell Island.

There was considerable German submarine activity in the area

of Anticosti Island. This was no sooner passed on the Canadian Navy when, two

nights later, the Caribou, a Newfoundland passenger boat, was sunk in the Gulf

with a big loss of life. “I certainly felt awfully bad when I heard the Caribou

was gone,” he said.

Saying how important the war effort at Gander must have been,

he recalled that radio operators also monitored activities of the famous German

battleship Bismarck, which was eventually sunk by the British.

During

the last year of the war, Mr. Dempsey and his family took up new residence.

They moved to an apartment in a building known as the Mars Building. It was

close to where the vacated EPA premises are now.

During

the last year of the war, Mr. Dempsey and his family took up new residence.

They moved to an apartment in a building known as the Mars Building. It was

close to where the vacated EPA premises are now.

The advent of post-war meant winding down of wartime

activities and there were many changes in administration relative to this

change, with the ultimate change coming at confederation in 1949, when the

Canadian government took over the airport, but, in the interim, the more gradual

change meant the disappearance of the military, in favour of civilians taking

over. Former buildings for military use became available for civilian use, at

which time an establishment with a community look began spring up around the

airport.

There was already a popular night club, for its idea was

spawned at Botwood, although the club was never started there. Formation of

such a club came to mind as a means of socializing, so by the time, personnel

had moved to Gander from Botwood the idea was ready to take root. Known as the

Newfoundland Airport Club, it was officially opened November 30, 1938 and it was

the first liquor licenced bar ever in Newfoundland. There were pubs in St.

John’s, for instance, but these didn’t have bars.

Money was not used directly in purchases, however, at the

Airport Club. The practice was to buy books of stamps, at five dollars each and

these stamps were received in exchange for liquor or beer. Something else that

was peculiar. A customer could not patronize another by buying that customer a

drink. “He could only treat himself and that was the law,” was the way Mr.

Dempsey put it.

The Club had about 50 members and was located in rooms on the

first floor of the old administration building; the Club moved downstairs,

adding pool tables and a movie projector. A closed Club, members had to be

nominated, and then approved formally to be accepted.

In 1945 the Club took up new quarters at the lower end of

Chestnut Avenue down from Hangar 13 and in a building vacated by a construction

company. Later the Club relocated to a vacant Sergeants Mess near a bridge to

the army site. The final move for the Club in the old town was to the vacated

RCAF Officers Mess just west of Hangar 13.

The latest location of the time-honored Club is off the Trans

Canada Highway in the new town of Gander, where it was officially opened in

1960. One function of the Club was to hold a monthly dance with an orchestra

for teenagers.

Mr. Dempsey was vice-president of the Airport Club from

1951-1954 and president from 1954-1962. He selected the land where the Club is

now located and is honored as a life member of the Club.

In 1957 Mr. Dempsey introduced curling to Gander using the

old hockey rink, and then in 1952 two sheets were provided for curling at the

Airport Club. For his contribution to curling he has been honored by the

province, being elected to the Newfoundland Curling Hall of Fame, Builders’

category.

He also help organize broomball, playing it first on natural

ice in the old hockey rink, where the stadium is at present. At times, the game

was played with water on the ice, he recalled lightly, which hardly made it a

non-splash exercise.

Mr. Dempsey, who had been a radio supervisor from 1948 to

1953, retired in 1973, after spending the final 20 years as a radio technician.

When construction of the new town commenced he moved to a

home on Brochen St. where has resided ever since.

Compared with the closeness of community at the old town, he

finds the new and much larger Gander somewhat lonely. Reflecting on 50 years of

his life at Gander, he said about 75 percent of the people he had known have

passed away.

Not only that but old-time Gander, being closely knit, “was

better, was more social, not the same now as it was then.